Ustilago maydis attacks and reproduces in the aerial parts of the corn plant. Huge tumor-like tissue growth often form at the site of infection. These galls can reach the size of a child's head. The growths are triggered by molecules released by the fungus, called effectors. They manipulate the plant's metabolism and suppress its immune system. They also promote cell growth and division in corn. To do this, they interfere with a plant signaling pathway regulated by the plant hormone auxin.

"The fungus uses this auxin signaling pathway for its own purposes," explains Prof. Dr. Armin Djamei, who heads the Plant Pathology Department at the INRES Institute of the University of Bonn. "This is because the huge growth of the tissue devours energy and resources that are then lacking for defense against Ustilago maydis. In addition, the fungus finds an ideal supply of nutrients in the growths and can multiply well there." The formation of the characteristic galls is thus definitely in the interest of the pathogen.

"We therefore wanted to find out how the fungus promotes these proliferation processes," says Djamei. "To do this, we searched for genetic material in the fungus that enables it to control the auxin signaling pathway of its host plant and thus its cell growth." The complex search began seven years ago at the Gregor Mendel Institute in Vienna. Later, the crop researcher continued the work at the Leibniz Institute in Gatersleben and later at the University of Bonn.

Pathogen reprograms its host

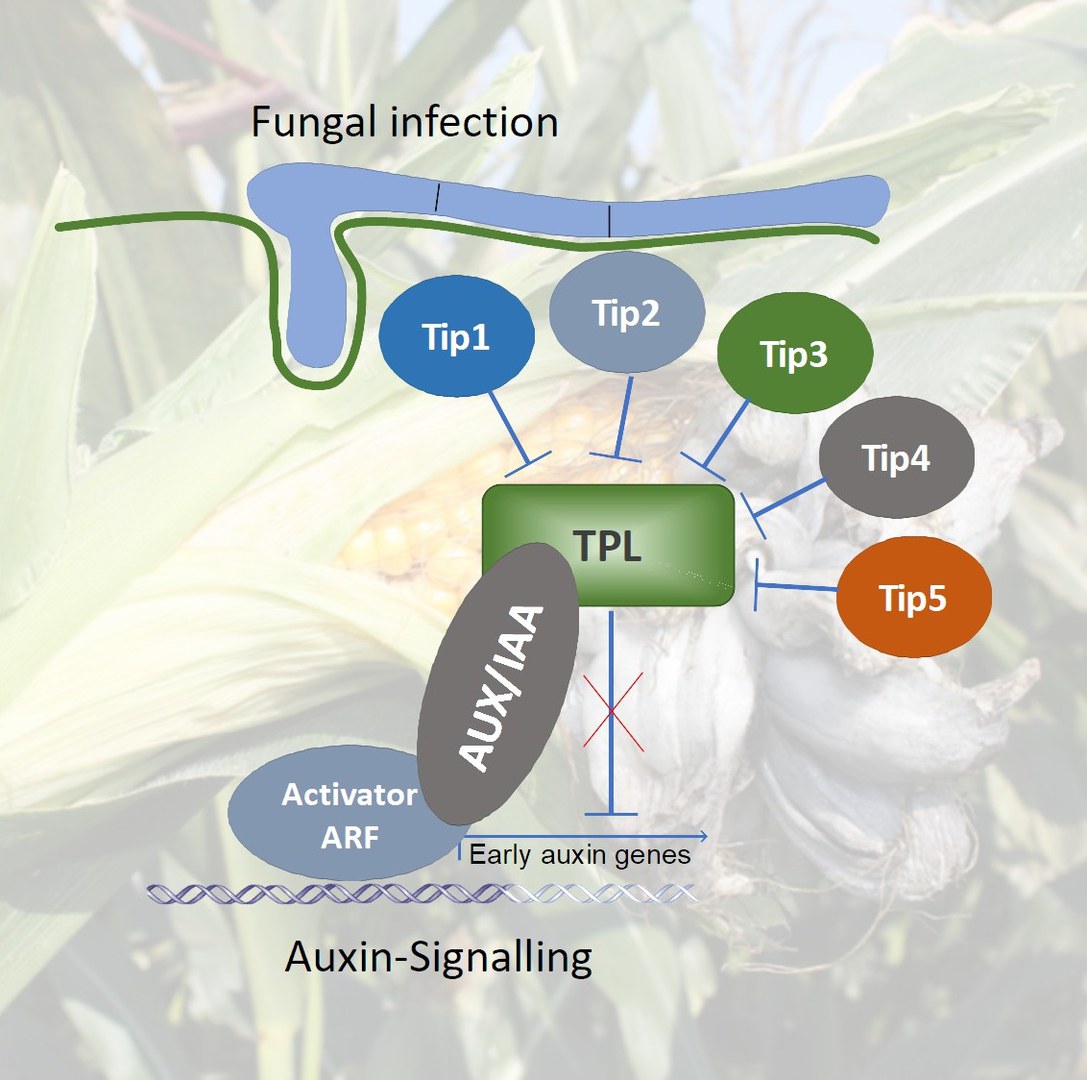

With success: Together with his collaborators, he was able to identify five genes that the fungus uses to manipulate the host plant's auxin signaling pathway. These five genes, called Tip1 to Tip5, form what is known as a cluster: If one imagines the entire genome of Ustilago maydis as a thick encyclopedia, these five lie, as it were, on successive pages.

Genes are construction manuals - the fungus needs them to produce respective proteins. "The proteins encoded by the five Tip genes can bind to a protein in the corn plant known to experts as Topless," explains Dr. Janos Bindics. A former employee of the Gregor Mendel Institute, he and his colleague Dr. Mamoona Khan performed many of the study's key experiments.

Topless is a central switch that suppresses very different signaling pathways in the plant. The fungal effectors produced by the five Tip genes override this repression - and do so very specifically for signaling pathways that benefit the fungus, such as the auxin-driven growth signaling pathway. In contrast, other signaling pathways controlled by Topless are not affected. "Figuratively speaking, the fungus acts with surgical precision," stresses Djamei. "It accomplishes exactly what it needs to accomplish to best infect the corn plant."

Insights for basic research

There are a number of pathogens that interfere with the auxin signaling pathway of the hosts they infect. Exactly how is often not fully understood. It may be that Topless plays an important role in this process in other crops as well. After all, the protein originated several hundreds of millions of years ago and its central role has hardly changed since then. It therefore exists not only in corn, but in a similar form in all other land plants. For example, the researchers were able to show that the Tip effectors of Ustilago maydis also interfere with the auxin signaling pathway of other plant species.

The findings could therefore help to better understand the infection processes in important plant diseases. The results are particularly interesting for basic research: "Through them, it will be possible for the first time to influence specific effects of the auxin signaling pathway in a very targeted manner and thus to elucidate the effect of these important plant hormones even more precisely," hopes Armin Djamei, who is a member of the Transdisciplinary Research Area “Sustainable Futures” and the PhenoRob Cluster of Excellence at the University of Bonn.

Funding and institutions involved

The study was funded by the European Research Council (ERC), the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), the Austrian Academy of Sciences, and the German Research Foundation (DFG). In addition to the University of Bonn, the Gregor Mendel Institute of Molecular Plant Biology in Vienna, the Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research in Gatersleben, and the University of Cologne were involved in the work.

Publikation: Janos Bindics, Mamoona Khan, Simon Uhse, Benjamin Kogelmann, Laura Baggely, Daniel Reumann, Kishor D. Ingole, Alexandra Stirnberg, Anna Rybecky, Martin Darino, Fernando Navarrete, Gunther Doehlemann & Armin Djamei: Many ways to TOPLESS – manipulation of plant auxin signalling by a cluster of fungal effectors; New Phytologist; https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.183151

To the press release of the University of Bonn:

www.uni-bonn.de | 10.08.20222